"While Jesus was having

dinner at Levi’s house, many tax collectors and sinners were eating with

him and his disciples, for there were many who followed him." (Mark 2:15)

I’m guessing this story is the basis for the “Jesus

parties” used as an evangelistic tool in the 90s.

You invite all your friends over for food and games, and then when everyone’s

having a good time, climb a soapbox, and ambush them with a sermon about their

sin. The difference between that and Levi’s party? Levi’s open house flows

naturally and honestly out of who and where he is.

When I was at writing school in Saskatchewan this

May, I was surrounded by diverse people - Daoist, pantheist, atheist - some of them had grown up in church and Christian camp and now felt

like they’d been there/done that/moved on. I struggled with when to say things

about my faith. I didn’t want to silence a big part of myself, but I was

horrified at the thought of making my new friends feel like stickers on a Sunday

school witnessing chart. I decided all I could do was invite the Spirit into my

conversations. If the idea popping into my head was something I’d share with my

Christian friends, like adding how God cares for fallen sparrows into a

conversation about the symbolism of birds, I’d say it. If it felt defensive or

contrived, I’d leave it out.

Mark says, “Many tax collectors and ‘sinners’ were

eating with Jesus and his disciples.” It’s not the religious leaders who first call

this group sinners, but Mark himself. Mennonite scholar Tim Geddert suggests perhaps

that these aren’t just people the pious would find ceremonially incorrect, but

those “known as notorious sinners, those who would agree that the designation

suits them.”

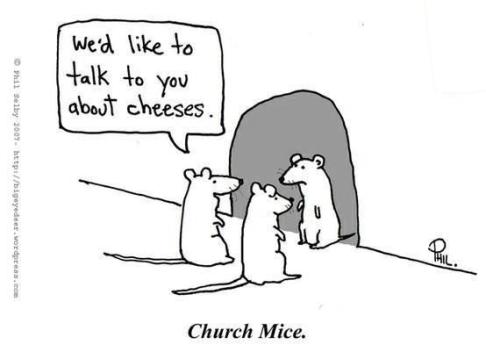

Like the two Muppets in the balcony, the Pharisees

jump in with heckles, criticizing Jesus to his disciples for eating with

"sinners." Why are the Pharisees even there? Were they following Jesus or did

they just happened by? Dining rooms were often adjacent to courtyards, it

would’ve been easy for passersby to eavesdrop.

The Pharisees' critique is a valid one. If you want

to be a public figure, a respected teacher, you’re going to be judged by the

quality of your followers. My family was asked to leave a music class once

because if we didn’t, the other families were threatening to pull out their

children. Jesus’ choice to include the socially unacceptable followers meant he

might lose the upstanding ones, along with his reputation in the synagogue.

Jesus responds with a popular Greek and Hebrew proverb: “It is not

the healthy who need a doctor but the sick.” In the Jewish form, God is

physician. Interesting choice of metaphor, since he’s spent the

last chapter trying to get away from the crowds seeking him as doctor, instead

of teacher.

But here Doctor Jesus isn’t healing just individual

bodies, but a community. We’d all love for Jesus to heal broken parts in our

bodies and minds, and I believe he does heal, more often than we’re comfortable

talking about. But here, “The [doctor] image implies that, whereas the

critics see sinfulness as something simply to exclude and avoid - and certainly

to judge and condemn - for Jesus ‘sinners’ are sick people in need of inclusion

and healing,” writes Brendan Bryne.

It's politically incorrect to call people “sick”

today, until we truly acknowledge that this means all of us, and that “patient

in treatment,” when Jesus is the physician on call, is very hopeful indeed.

Jesus’ statement “I have not come to call the

righteous but sinners” takes us back to the call of Levi. Jesus doesn’t just

heal or call people to repent, he calls us to follow.

Which is Levi: a sinner or a disciple? The irony is

that Levi and many of the other guests are already disciples, not sinners; it’s

no longer possible to draw a rigid distinction. Pharisees categorized people as

sinners and righteous, tax collector and teacher; Jesus is forming a new

household that rejects labels.

So is Jesus saying he’s only interested in those who

know they’re sinners, not the self-proclaimed “righteous”? No, his focus is

those who’ve been rejected, but he includes everyone in that, even the

pompously self-righteous (who today are most likely among the rejected!). I

think he’s saying, between the families threatening to leave the music class,

and my own needy, quirky one, he’d include us and let the other families

choose.

Conclusion in the next post.

Conclusion in the next post.

No comments:

Post a Comment